INTRO VOL.01

Introduction to reconciliation

Introduction to reconciliation

INTRO VOL.01

Hi… welcome to:

An incredible journey with Musalaha. Through this first course, you will join a diverse group of individuals from various ethnic and religious backgrounds, all working towards healing and unity.

begin course belowIntroduction to reconciliation

PDF Download

Download the PDF to start your journey—build bridges, spark dialogue, and make an impact. Use it to navigate The in your online course alongside the videos below.

Download PDFRegister

Free

Join the Musalaha Academy at no cost and gain access to additional content and tools designed to enrich your learning journey.

RegisterWelcome to Musalaha’s Reconciliation: A Guidebook for the Transformation of Conflict. Before delving into your journey towards reconciliation, we want to introduce you to Musalaha’s vision, role, and mission. We work for reconciliation in Palestine and Israel, navigating through conflict, occupation, prejudice, pain, inequality, fear, and hate, on a daily basis…

Reconciliation doesn’t occur naturally under systems of oppression like apartheid, settler colonialism, or military occupation. In contexts like Israel-Palestine, physical separation, legal restrictions, and political control prevent meaningful interaction, while narratives rooted in fear and superiority reinforce division. Both legal structures and manipulated ideologies work together to maintain inequality and block pathways to peace.

Musalaha begins its reconciliation journey by taking Israelis and Palestinians into the Jordanian desert—a neutral, quiet space free from checkpoints, media, and daily pressures. In the vastness of Wadi Rum, power imbalances fade as all face the same physical challenges, encouraging vulnerability, trust, and empathy. Stripped of distractions, participants begin to see each other’s humanity through shared experiences and joint reliance. Spiritually, the desert becomes a place of transformation—echoing moments in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions where the wilderness was a place of deep encounter, reflection, and identity change.

Musalaha’s reconciliation process unfolds over a series of weekend workshops led by both Israeli and Palestinian facilitators. Through guided dialogue, participants confront personal and collective barriers, explore history and power dynamics, and reshape their understanding of identity. The journey challenges both sides to seek truth, embrace accountability, and commit to non-violent co-resistance rooted in empathy and shared humanity.

- Process and/or Outcome

- Structural and/or Relational

- Top-Down and/or Bottom-Up

- Interpersonal and/or Intergroup

- Maximal and/or Minimal

- Ideal and/or Non-Ideal

- General and/or Contextual

Throughout history, sacred texts have offered wisdom, comfort, and challenge—calling humanity toward justice, compassion, and peace. Across faith traditions, these writings remind us that peace is not just the absence of conflict, but the presence of right relationships, mercy, and hope. Below is a selection of verses and teachings from religious scriptures that speak into the heart of reconciliation, inviting us to be peacemakers in a world that often forgets how.

Sulha is an ancient Middle Eastern practice of conflict resolution rooted in Arab culture, emphasising honour, reconciliation, and third-party mediation—though its communal and relational approach can be difficult to translate into Western legal systems.

All our sources and references in the Academy are carefully selected from credible academic publications, peer-reviewed journals, and expert contributions. Each reference is cross-checked to ensure our materials remain accurate and reliable.

Course Footnotes

Footnotes provide additional information and direct links to related resources used in this course.

—

[1] M. Freeden, “Ideology”, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, DOI:10.4324/9780415249126-S030-1.

—

[2] Yoav Gallant, Israel’s Minister of Defence, Speech, 9th of October 2023. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/israel-palestine-war-fighting-human-animals-defence-minister.

—

[3] Linda Radzik and Colleen Murphy, “Reconciliation”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/reconciliation/>

—

[4] Hanafi, Sari. Dancing Tango During Peacebuilding: Palestinian-Israeli People-to-People Programs for Conflict Resolution, in Beyond Bullets and Bombs, ed. Judy Kuriansky. (Praeger Publishers, 2007), pp. 69. See also Rabah Halabi and Nava Sonnenschein, “School for Peace: between Hard Reality and the Jewish-Palestinian Encounters,” in Beyond Bullets and Bombs, ed. Judy Kuriansky (Praeger Publishers, 2007), pp. 278–279.

—

[5] Doubilet, Karen. Coming Together: Theory and Practice of Intergroup Encounters for Palestinians, Arab-Israelis, and Jewish-Israelis, in Beyond Bullets and Bombs, ed. Judy Kuriansky (Praeger Publishers, 2007), pp. 52.

[1] M. Freeden, “Ideology”, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, DOI:10.4324/9780415249126-S030-1.

—

[2] Yoav Gallant, Israel’s Minister of Defence, Speech, 9th of October 2023. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/israel-palestine-war-fighting-human-animals-defence-minister.

—

[3] Linda Radzik and Colleen Murphy, “Reconciliation”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/reconciliation/>

—

[4] Hanafi, Sari. Dancing Tango During Peacebuilding: Palestinian-Israeli People-to-People Programs for Conflict Resolution, in Beyond Bullets and Bombs, ed. Judy Kuriansky. (Praeger Publishers, 2007), pp. 69. See also Rabah Halabi and Nava Sonnenschein, “School for Peace: between Hard Reality and the Jewish-Palestinian Encounters,” in Beyond Bullets and Bombs, ed. Judy Kuriansky (Praeger Publishers, 2007), pp. 278–279.

—

[5] Doubilet, Karen. Coming Together: Theory and Practice of Intergroup Encounters for Palestinians, Arab-Israelis, and Jewish-Israelis, in Beyond Bullets and Bombs, ed. Judy Kuriansky (Praeger Publishers, 2007), pp. 52.

Congratulations for finishing

Note got here to come

Note got here

Status: Finished

Congratulations on completing:

Introduction to reconciliation

Hi… Guest

—

Reconciliation is a way forward, small faithful steps that can help change the world.

What you have learned today can ripple out to your family, community, and beyond.

“Peace is built together, one restored relationship at a time.”

Keep going, your next step is waiting in the Academy.

Musalaha Sincerely

Academy

Feedback:

Dear

welcome…

Welcome to Musalaha’s Reconciliation: A Guidebook for the Transformation of Conflict. Before delving into your journey towards reconciliation, we want to introduce you to Musalaha’s vision, role, and mission. We work for reconciliation in Palestine and Israel, navigating through conflict, occupation, prejudice, pain, inequality, fear, and hate, on a daily basis.

During your journey, you will begin to notice that reconciliation is everywhere. More so, the need for reconciliation is present in even the smallest and most seemingly insignificant events and encounters. Reconciliation drives us to reflect on and critically assess our role within a collective. What is my humanity? What is my position of power? Am I oppressing others or are others oppressing me? Who am I and how does my identity affect those around me? There are plenty of interpretations of what reconciliation is, what it means, and what it should look like.

In the case of Musalaha, we are a faith-based organization that teaches, trains, and facilitates reconciliation mainly between Israelis and Palestinians from diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds, based on biblical principles of reconciliation.

We believe that in the case of Palestine and Israel, reconciliation looks like:

“An indigenous process of restoring relationships between groups of (perceived) enemies by healing together. Healing implies redefining the self, power constructs, and the conflict, through a profound identity and narrative transformation. This transformation begets concrete steps towards non-violent liberation of the oppressed, and redemption of the oppressor, in co-resisting injustice together based on true equality and humanity.”

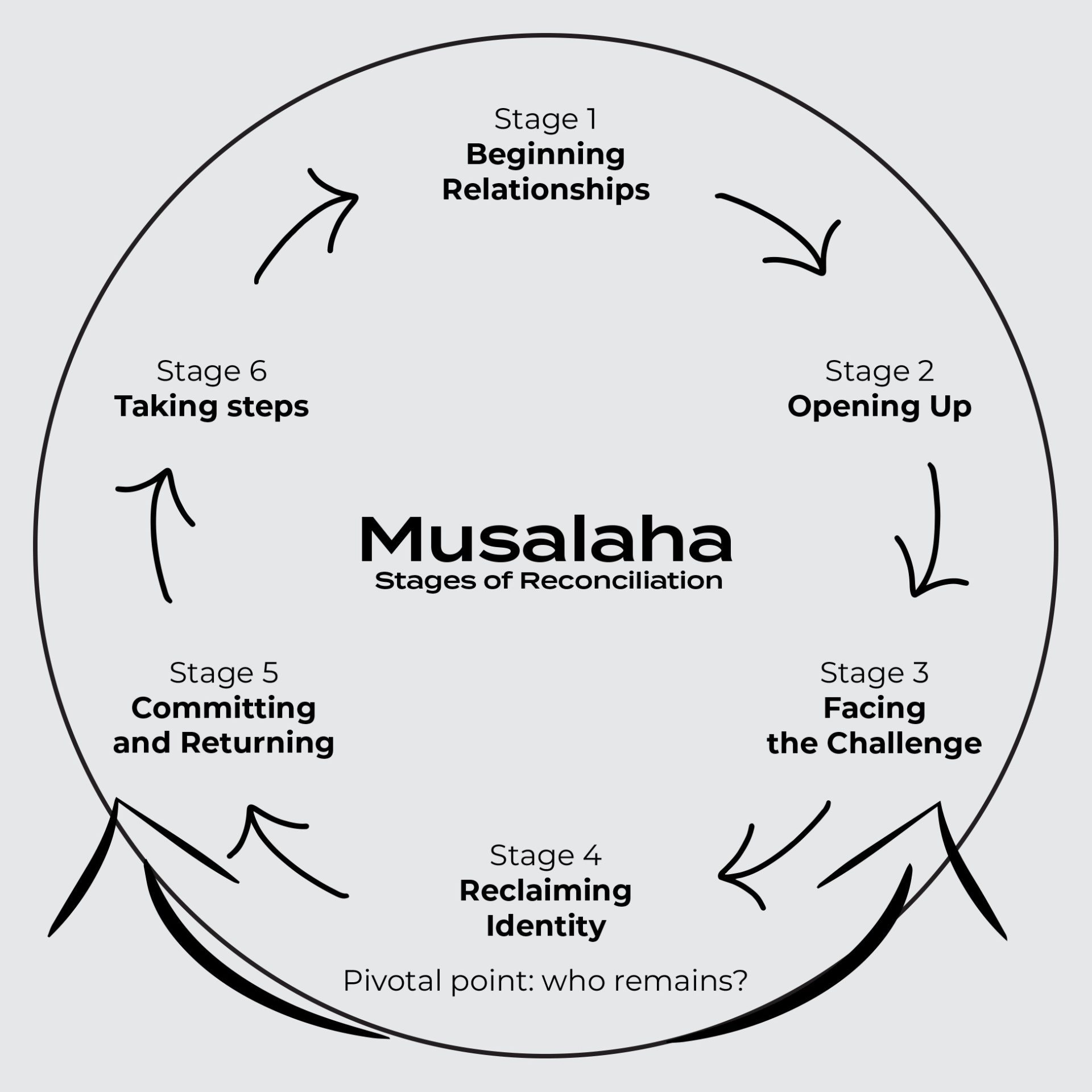

While reconciliation is often mistakenly perceived as linear, Musalaha posits it is a dynamic and fluid process. As reconciliation is sensitive and–at times–confrontational for both groups and individuals, we encourage people to progress slowly and mindfully, conscious of the challenges ahead. In case someone feels lost for a prolonged period, it is recommended to take a step back. If we do not regress into old views and give up altogether, our journey is worth it. Even failure to reconcile can be rewarding and a step towards reconciliation in itself. From experience, we witnessed some individuals first resist and withdraw from the process only to rejoin ready to challenge their self-perception, change relationships, and grapple with unjust power systems and structures.

Take a deep breath and walk with us through the pages ahead, as you begin your reconciliation journey.

Musalaha’s Reconciliation: THe Problem

Reconciliation in systems of oppression–such as dictatorships, totalitarian regimes, despotism, settler colonialism and apartheid–does not happen organically. Those in power impede the oppressor and oppressed from interacting and challenging power structures that benefit the elite and the powerful. Cementing an imbalance of power is crucial for maintaining inequality and creating intentional obstacles to reconciliation.

In Musalaha’s context, there is very little physical space available for Palestinians and Israelis to meet. Palestinians’ freedom of movement is extremely limited, as they are confined in locked-in areas entirely controlled by Israel and Egypt (Gaza), under military occupation controlled by military checkpoints and a separation wall (West Bank, Gaza), or they live in Israel as second-class citizens with fewer political, civil, and socio-economic rights and segregated education (in Jerusalem and Palestinian cities/towns in Israel). The Israeli government imposes laws and practices that separate and segregate people based on their ethnicity and religion. Ever since the Oslo Accords in 1993-1995, the West Bank has been divided in Area A (civilian and military authority by the Palestinian Authority), Area B (civilian authority by the Palestinian Authority and military authority by the Israeli government), and Area C (civilian and military authority held by the Israeli government). Israeli military law prohibits Israelis from entering Gaza and Area A in the West Bank.

The Palestinian Authority, the governing body of Area A and partially of Area B in the West Bank, has severely restricted the independency of Palestinian movements and non-profits in the West Bank. The Palestinian Authority’s laws require that both civil society and foreign donors’ donations must be invested in the PA, increasingly nationalizing and rendering peace initiatives unworkable.

Laws that separate and segregate based on ethnicity find their legal basis in Israel’s 2018 Nation-State Basic Law. This law excludes the right of self-determination for all non-Jewish residents in Israel, allocates national value to settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, and establishes Hebrew as the sole official language of Israel. This law is one of the many expressions of exclusivist ideologies and ethno-centric supremacy.

Besides legal and physical obstacles, both the oppressor and oppressed often suffer from underlying emotional and psychological barriers when seeking to reconcile. Fear and misunderstanding of the “other”–whether based on religion, background, ethnicity, gender–tend to be intentionally exploited by oppressive leadership. This exploitation supports the construction of a perceived rational, exclusivist, and legitimate ideology.

Scholars generally define “ideology” as “a set of ideas, beliefs, and attitudes that reflect and shape understandings or misconceptions of the social and political world. Ideologies serve to recommend, justify or endorse collective action aimed at preserving or changing political and economic practices and institutions that form society.” [1] Examples of ideologies are nazi-socialism, socialism, liberalism, communism/Marxism, and capitalism.

One of the most effective means to present and justify ideologies is through (manipulative) narratives. Narratives help to develop a lens to perceive yourself and your worldview within a larger context of an ideology. In an oppressive system, narratives are often “zero-sum,” meaning that these narratives interpret historical events for the benefit of one group at the expense of the other. Zero-sum narratives leave no room for opposing information to exist and monopolize the truth, justifying exclusivist ideologies.

These narratives often dehumanize, demonize, and trivialize the basic human needs of the “other” while seeking to victimize the oppressor. Examples of said narratives are any racist and discriminating accounts depicting all Jews, Muslims or Christians as the natural enemy or, in some cases, “terrorists,” ignoring their fundamental human needs and rights. Other narratives sever any connection of indigenous people to their land by referring to them as “aliens,” and pass their natural territorial claims to settlers (i.e. process of reverse alienation). “Naturalization”–the need for immigrants to prove their “natural” rights before they are allowed to integrate–is another example of a successful narrative often held by members of a Western host country. Some narratives exclusively recognize one religion at the expense of others or grant more rights to a group of people based on specific physical or ethnic traits.

Whereas narratives of oppression must be challenged and criticized, narratives of the oppressed cannot escape scrutiny. Often, the oppressed respond to injustice by creating narratives that promote violent revenge to correct past and current injustices. These narratives can also be zero-sum, perpetuate violence, and lack a just and humane response. For example, these narratives seek to justify war crimes, religious/ethnic supremacy, and violent resistance against civilians, based on the inferiority and the alleged evilness of all members of the “enemy side.” Consequently, reconciliation remains unattainable.

In the context of Musalaha, the Israeli political elite structures narratives seek to dehumanize the enemy and aim to exploit generational trauma. These narratives amplify existential fear and justify Israel’s defensive war against an antisemitic enemy. Moreover, the settler-colonial narrative seeks to erase the Palestinian identity and collective memory through collective punishments such as mass detentions, raids, and silencing policies. Meanwhile, Israel seeks to trivialize Palestinian indigenous connection to the land by legalizing Israeli settlements and demolishing Palestinian homes. A phrase commonly used within religious militant-Zionist circles is the following: “Israel was a land without a people, and the Jews were a people without a land.” Israeli ministers have publicly dehumanized Palestinians and compare them to “human animals.” [2]

Part of the Palestinian response is to self-isolate and abandon political life. Others harshly equate any encounter with Israelis by “normalization,” as they believe that all interaction immediately and necessarily damages the Palestinian call for justice, while legitimizing Palestinian suffering. Although normalization does occur frequently, the equation of any encounter, even for the sake of equality, liberation, and redemption, with normalization, makes the victim into the oppressor, acting out a narrative of exclusion. Besides normalization, some Palestinians respond by racism and dehumanization. Others have resorted to religious militarism, and violent resistance, denying the value of Jewish life and their basic human rights, while glorifying antisemitism. Some have responded by collaborating with the oppressor, abandoning their call for justice entirely.

Musalaha’s Reconciliation: The Desert

During the first stage of reconciliation, Musalaha brings together Israelis and Palestinians for a multi-day encounter in the Jordanian Wadi Rum desert. The location of the desert has been intentionally chosen to begin relationships between people who are perceived as enemies and to lead them to forge authentic relationships.

Musalaha uses the desert as a safe space of encounter and inclusion between Israelis and Palestinians, as it removes individuals from military checkpoints, arrests, attacks, media access, social expectations; and cultural/social restrictions. Due to its remote and quiet location, the desert facilitates open and constructive interaction as both Israelis and Palestinians detach from daily tensions.

In its stillness and vastness, people have the opportunity to shake off prejudice and opinions and start to explore “the other” on neutral ground. The desert remedies the power imbalance, as its harsh climate tests everyone equally. Gender, ethnicity, race, socio-economic class, and materialistic possessions become less relevant. Submersed into Bedouin (from the Arabic word “Badawi”, meaning “desert-dweller) life and subjected to the natural elements, individuals are guided to uncover humanity because they are more vulnerable. With limited data connection and access to running water, individuals rely upon each other for basic comfort and needs. This dependency is a crucial foundation for future bonding and establishing sustainable relationships built upon trust and empathy. Joint physical challenges, such as hikes, camel rides, and jeep tours, further nurture this experience.

From a theological perspective, the desert solicits a transcendental metamorphosis by evoking deep reflections. The Hebrew word for desert is “midbar” derived from the Hebrew verb “to speak,” or “ledaber.” “Midbar” and “ledaber” share the Semitic root, “dvar,” meaning “place where God spoke to people in the Bible.” The desert invites people to speak, be uncomfortable, reflect, grow, and transform their identities.

In all Abrahamic indigenous theologies, the desert has transformative power in human relationships and with God. In Jewish tradition, Moses received God’s message in the desert, transforming his identity and readying him to confront Pharaoh and then led the enslaved Israelites through the desert on their path to freedom. John the Baptist began his ministry in the desert, preaching a message of repentance far from the religious establishment where he was tempted; and similarly, Jesus, immediately following his baptism, proceeded into the desert. Early Islam was birthed in the desert as the Prophet of Islam, Mohammed, was an Arab caravan driver, his mind heavily occupied with desert imagery.

Musalaha’s Reconciliation: The Rest of the Journey

Upon returning from the desert, Israelis and Palestinians continue with the next 5 stages of reconciliation.

Each stage is implemented through one or two weekend reconciliation trainings, as all individuals engage in facilitated conversations about chapters in Musalaha’s Curriculum for Reconciliation. All conversations are guided by one Palestinian and one Israeli leader, aiming to create a power balance and minimize competition between both groups as they are equally represented by a local community member. Musalaha’s reconciliation workshops usually take place in Area C in the West Bank, as this is one of the few places left for physical encounters between Israelis and Palestinians. Almost all meetings are conducted in Hebrew and Arabic.

During stage 2–and the first weekend reconciliation training–all individuals learn to “Open Up” by tackling physical, psychological, emotional, and ideological obstacles to reconciliation. In this stage, the Palestinians tend to open up and unload their grievances on the Israelis, while the Israeli individuals want to focus on relationship building. This stage tests newly formed relationships for the sake of future co-resistance.

The second reconciliation weekend workshop tackles “Conflict Analysis” and teaches truth by means of presenting the participants with new information, or old information in a new way. Some people tend to regress or withdraw from reconciliation as their perception of the conflict, and themselves, is being challenged. The most pivotal second and third workshops delve into “History” and “Narrative”, and their role in conflict. During these workshops, people continue to “Face the Challenge” as they are confronted with settler-colonial and native narratives. In order to effectively co-resist oppressive structures and systems, all those in reconciliation must correctly analyze and identify root causes and inherent characteristics to said structures and systems”. Attitude change is required for the oppressor to abandon their positions of comfort, while oppressed and oppressor must critically self-reflect and question authority. Together, identities and relationships are renegotiated, based on a transformed narrative.

During the fifth weekend reconciliation training, Israelis and Palestinians learn about “Identity” and “Power” as they Reclaim their Identity. An in-depth understanding of the power imbalance and societal labels is developed, and all individuals learn to critically approach their own identity and its consequences on the “other.” Israelis and Palestinians learn about the relevancy of language, identifying imperialistic, colonial, violent, and vengeful language.

After these pivotal workshops, people either decide to withdraw or to “Commit and Return”. Those that remain in reconciliation are able to recognize their own people’s shortcomings and actively seek to restore truth based on historical responsibility, authenticity, and personal accountability. During the sixth and final weekend reconciliation training, the individuals are trained in “Non-Violent Co-Resistance”. This pragmatic workshop requires all individuals to brainstorm, discuss and select best strategies and outreaches to publicly non-violently co-resist systematic injustices, in the interest of their own and the other community.

Finally, Musalaha’s reconciliation journey concludes with “Taking Steps.” Through joint Israeli-Palestinian action, all those involved seek to effectively, publicly, and non-violently co-resist oppressive and unjust structures and systems. This said, all action aims to correct wrongdoings and liberate the oppressed. In order to liberate, all action is designed towards developing a shared society based on true equality between ethnic and religious groups, and a fundamental respect of and for all human rights, needs, and duties. Examples of these action-taking initiatives are public speaking engagements and education, artistic expression, environmental campaigns, demanding for social and political change.

Musalaha’s reconciliation journey usually spans over a couple of months to one entire year. However, reconciliation lasts, grows, and transforms with our lives. Like our faith, belief, growth, knowledge, and relationships, reconciling ourselves is always in motion.

Musalaha’s Reconciliation: What is Reconciliation?

When attempting to define reconciliation, many other related concepts, such as truth, forgiveness, reparation, recognition, peace, and justice, come to mind. Although intertwined, these concepts are not interchangeable. Instead, they are clearly distinct and even contradictory at times. Some might believe forgiveness is necessary during the process of reconciliation, while others believe that one can forgive without reconciling.

Scholars Linda Radzik and Colleen Murphy point out, “Critics charge that the language of reconciliation lends itself to misuse. Given that the concept has no widely recognized, determinate content or clear normative standards, almost anyone can claim to be pursuing reconciliation. Nevertheless, defenders of the concept of reconciliation believe that it is amenable to further articulation.” [3]

The concept of reconciliation has been employed in several contexts. Some non-exhaustive examples include:

- religious, such as Christianity’s notion ofreconciling oneself with Christ and in the context of redemption and repenting sin;

- political, such as South Africa’s transition from apartheid to democracy;

- in liberation movements; and

- personal, when reconciling with a spouse, friend or coworker. The emphasis on reconciliation, especially in political contexts, can either be motivated by religious and moral values, or used solely for the sake of political gains.

There are several theoretical lenses that remind us of the multi-dimensional concept of reconciliation. It is important to note that these theoretical lenses are not meant to be mutually exclusive. Instead, they can be helpful tools depending on the context in which you are reconciling. Musalaha believes that reconciliation is a dynamic and fluid process and that defining reconciliation–both its function and meaning–is part of the process of reconciliation itself. We invite you to struggle through a few exercises that guide in theoretically defining reconciliation.>

PROCESS AND/OR OUTCOME:

One of the main theoretical exercises in defining reconciliation is to distinguish whether reconciliation is a process or an outcome. Scholarly opinions vary and suggest both possibilities. In case reconciliation is a process, then the focus lies upon the steps taken to achieve reconciliation; whereas if it is an outcome, one should focus on what is achieved at the end of the process.

STRUCTURAL AND/OR RELATIONAL:

This binary distinguishes between the structural and relational approaches. Whereas the structural approach focuses on changing the institutional or systemic factors that contribute to conflict, the relational approach focuses on rebuilding relationships between individuals or groups.

TOP-DOWN AND/OR BOTTOM-UP:

This approach distinguishes between processes that are initiated by those in power, such as governments or institutions, and reconciliation that is instigated by grassroots movements and affected communities. When reconciliation is directed by those in power, it tends to endanger the establishment of equal relationships and instead results in superficial contexts or submission of one side to the other. Meanwhile, grassroots reconciliation can mean liberation and justice for the oppressed.

Reflections:

Please log in to save answers.

INTERPERSONAL AND/OR INTERGROUP:

This binary distinguishes between approaches that focus on reconciliation at the individual level, such as between two people in personal conflict, and approaches that focus on reconciliation at the collective level, between groups or nations.

MAXIMAL AND/OR MINIMAL:

Maximal conceptions of reconciliation require a complete restoration of the relationship between conflicting parties and might include forgiveness, reparation, and recognition. An example of maximal conceptions would be the indigenous Arabic model of reconciliation or “sulha” . Minimal conceptions, on the other hand, only require a cessation of hostilities or the establishment of a peaceful coexistence between the parties. Minimal conceptions are often “Top-Down” Reconciliation initiatives, such as conflict mediation between two nation states, sometimes leading to peace formalized in treaties.

IDEAL AND/OR NON-IDEAL:

Ideal conceptions of reconciliation require that all parties fully embrace the process and the outcome. In contrast, non-ideal conceptions acknowledge that parties may not be willing to participate fully or that the outcome may not fully meet everyone’s expectations, as occurs in divorce or inheritance mediations, or other court-mandated reconciliation processes.

GENERAL AND/OR CONTEXTUAL:

Another theoretical question requires us to distinguish between general and contextual conceptions of reconciliation. General conceptions of reconciliation attempt to provide a universal definition that applies to all situations, whereas contextual conceptions recognize that the meaning of reconciliation may differ depending on the specific context in which it is used.

Exercise:

Recall a recent conversation that was difficult or possibly even an argument. Rate your ability in practicing leveling from 1-5 (1: not good, 5: excellent).

Research different cultural or religious approaches to reconciliation. How do they differ from each other in their understanding of reconciliation?

Please log in to save answers.

Do they prioritize a general or a contextual approach?

Please log in to save answers.

Considering the above, Musalaha pro-poses an intentional, two-dimensional approach to reconciliation:

The brokenness—generational trauma, fear, hatred, and is understanding—between Israeli and Palestinian people must be healed. Through prolonged encounters, individuals from both groups start to humanize one another by learning about each other’s realities, narratives, and identities. [4] Bonding and caring for one another despite differences teaches people to love their neighbor regardless. People learn to rebuild trust and reclaim identities to bless their neighbors. Demanding justice without any inner healing would lead to revenge and perpetuate cycles of violence, such as the world witnessed on October 7, 2023.

Discussion/Question:

Please log in to save answers.

Taking a joint and active stance against systemic injustices, including the root causes of settler colonialism, military occupation, and apartheid structures. [5] This stance has materialized through grassroots, tangible steps taken toward social and political justice in Israeli and Palestinian communities. While executing these steps, both the oppressed and the oppressor must contribute to the liberation of all people involved in the conflict.

Discussion/Question:

Please log in to save answers.

Musalaha’s Reconciliation: Sacred Texts about Peace and Reconciliation

IDEAL AND/OR NON-IDEAL:

Ideal conceptions of reconciliation require that all parties fully embrace the process and the outcome. In contrast, non-ideal conceptions acknowledge that parties may not be willing to participate fully or that the outcome may not fully meet everyone’s expectations, as occurs in divorce or inheritance mediations, or other court-mandated reconciliation processes.

According to Confucius, reconciliation regulates harmony and loyalty between humans. True ‘benevolence’ means extending love to all people in society beyond our own family, requiring us to treat strangers how we would want to be treated ourselves. Conflicts should be resolved through forgiveness, building trust, and mutual understanding. Instead of seeking revenge, the focus must be on restoring harmony and balance, emphasizing healing and rebuilding relationships based on ethics and community.

“Blessed are the peacemakers”

(Matthew 5:9)

Buddhism teaches us that reconciliation requires reestablishing trust. If I deny responsibility for my actions or maintain that I did no wrong, there’s no way we can be reconciled. Similarly, if I insist that your feelings don’t matter or that you have no right to hold me to your standards of right and wrong, you won’t trust me not to hurt you again.

“If one repents out of fear, the intentional sins are turned into unintentional sins. But if one repents out of love, the intentional sins actually become merits.”

(The Talmud)

“The believers are brothers [and sisters], so make peace between your brothers and be mindful of God so that you may receive mercy.”

(Qur’an 49:10)

The traditional, Middle Eastern, and indigenous Arab method for reconciling conflicts is called “Sulha”. Its historical roots are found in early Semitic writings and in later Christian records dating from the first century A.D. “Sulha” is typical of Arab desert culture and literature. The “Sulha” practice has endured generations—despite contextual modernizations—because it is based on common principles and collective wisdom typical of pluralistic communities. Its practice has formed across religious, political, and ethnic differences in the Middle East. Today, “Sulha” reinforces civil social order, respect, and reconciliation in culture and religion can you give?

Musalaha’s Reconciliation: SULHA

The traditional, Middle Eastern, and indigenous Arab method for reconciling conflicts is called “Sulha” . Its historical roots are found in early Semitic writings and in later Christian records dating from the first century A.D. “Sulha” is typical of Arab desert culture and literature. The “Sulha” practice has endured generations—despite contextual modernizations— because it is based on common principles and collective wisdom typical of pluralistic communities. Its practice has formed across religious, political, and ethnic differences in the Middle East. Today, “Sulha” reinforces civil social order, respect, and reconciliation among feuding community members, including families, neighborhoods, and individuals. A third-party mediator conducts a “shuttle diplomacy” between the conflicting parties, and addresses all dimensions of the conflict: psychologically, socially, economically, spiritually, cultural sensitivity, attitudes, feelings, and emotions. Once an agreement is reached, it is binding.

Important to note is that “Sulha” is not readily applicable in Western cultures and power structures. For example, women rarely occupy authority positions within the process of “Sulha”, and their voices are insufficiently heard. Moreover, concepts of “honor” and “shame” are interpreted differently in various contexts and cultures, and often lead to undesirable outcomes in Western societies. Finally, reconciliation scholars still debate how to extrapolate “Sulha” concepts into modern, legal systems of nation states and international law. The relational focus of the “Sulha” is at times incompatible with the punitive orientation of

Western court systems.

References

Freeden, “Ideology”, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, DOI:10.4324/9780415249126-S030-1.

—

Yoav Gallant, Israel’s Minister of Defence, Speech, 9th of October 2023. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/israel-palestine-war-fighting-human-animals-defence-minister.

—

Linda Radzik and Colleen Murphy, “Reconciliation”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/reconciliation/>

—

Hanafi, Sari. Dancing Tango During Peacebuilding: Palestinian-Israeli People-to-People Programs for Conflict Resolution, in Beyond Bullets and Bombs, ed. Judy Kuriansky. (Praeger Publishers, 2007), pp. 69.

—

Rabah Halabi and Nava Sonnenschein, “School for Peace: between Hard Reality and the Jewish-Palestinian Encounters,” in Beyond Bullets and Bombs, ed. Judy Kuriansky (Praeger Publishers, 2007), pp. 278–279.

—

Doubilet, Karen. Coming Together: Theory and Practice of Intergroup Encounters for Palestinians, Arab-Israelis, and Jewish-Israelis, in Beyond Bullets and Bombs, ed. Judy Kuriansky (Praeger Publishers, 2007), pp. 52.